[smart_track_player url=”http://traffic.libsyn.com/insatiable/S3E2_-__Protect_the_Earth_and_Your_Health_with_Mustafa_Santiago_Ali.mp3″ social=”true” social_twitter=”true” social_facebook=”true” social_gplus=”true” social_linkedin=”true” social_pinterest=”true” social_email=”true”]

Read the transcript

(INTRODUCTION)

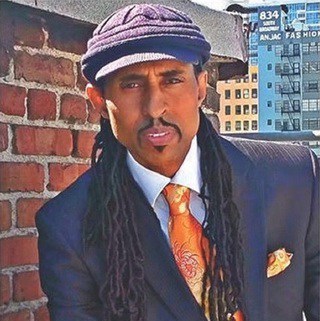

(0:00:08.8) AS: Welcome to season 3, episode 2 of the Insatiable Podcast: Protect the Earth and Your Health, with Mustafa Santiago Ali. I hear from so many of us that we want to protect the earth for its beauty, for our health, but the climate crisis is so massive, it can feel overwhelming and we often end up doing nothing. So I wanted to have Mustafa on. He is a renowned speaker, policy maker and member of the Environmental Justice Organization, hiphopcaucus.org. He is going to share with us today how we can get involved, have a lot of fun, and he shares some really inspiring stories of renewal when communities come together in the name of holistic environmental health. He has such a holistic approach and I think it’s really going to shift your focus and your mindset around what we mean when we want to work on the environment.

So today we’re going to talk about why focusing on rising temperatures or parts per billion of carbon isn’t actually the most effective way to get involved and what you can do instead. We’re going to talk about the power and approaching environmental justice holistically, especially for our most vulnerable communities and how it benefits all of us when we do that.

We’re going to talk about why Mustafa recently left the EPA after 20+ years. He left under the current regime and how you can keep your eyes wide open right now. With our current regime putting out so much propaganda for big polluters and what the EPA is slowly becoming. So I want you guys to know what’s happening so you aren’t caught making choices that seem healthy, but really aren’t, because the EPA is becoming a big corporate show. Lastly, we talk about Tupac, one of my favorite hip hop guys. Does he like him and does he think that he’s a prophet like I do? You’ll find out.

Before we get to the episode, a little bit more about Mustafa. He is a renowned speaker, policy maker, community liaison, trainer, advocate and critical thinker. He specializes in social and environmental justice issues and he’s focused on utilizing a holistic approach to revitalize vulnerable communities. He spent about 24 years at the Environmental Protection Agency, known as the EPA, and throughout his career he’s worked directly with over 500 domestic and international communities to improve lives by addressing environmental health and economic injustices.

Some other highlights; he has spoken and taught everywhere from Stanford to Howard and he’s been seen on MSNBC, CNN, VICE, Democracy Now, The New Republic, GQ, etc. So we were really lucky to have him and I think you’re really going to love this episode and have a different perspective on how you can get involved and protect the earth and your health.

Also, just a reminder, I just launched my new website at alishapiro.com and there’s a fun new quiz there where you can figure out your comfort eating style, and when you do that, take that quiz, as part of the tools that you get once you learn your new pattern, you’ll get an access to a secret Insatiable episode. So if you love the podcast, you will love this secret episode where I share a little bit of the intellectual property from Truce With Food, and you can get started today on ending your own comfort eating patterns. So enjoy that and enjoy today’s episode with Mustafa.

(INTERVIEW)

(0:04:08.5) AS: So, thank you so much for being here today, Mustafa. So many of our listeners, my clients, they get that environmental issues are basically the issues of our time, but it feels so big and like where do you even enter to make a difference and to know what is actually working versus brainwashing. So I really appreciate you being here today and bringing to much of your experience.

(0:04:32.9) MSA: Thank you so much for having me. Anytime we have the opportunity to sort of just share with folks, both the impacts and the opportunities that exist across our country. How people are making change? How people are reclaiming power? I mean, that’s what this is all about, each one teach one. Continuing to sort of just pass this information along and find places where fertile ground is.

(0:04:55.8) AS: Yeah. So how did you first get interested into the environment, because you have quite multiple decades of being aware of things? So how did you first find an interest in this?

(0:05:06.9) MSA: It probably started a number of different ways. One was with my father. My father was a big outdoorsman, so he always had me and my brother and my sister too, even though she was a little different in how she approached it. Just out fishing, hunting, hiking, camping, those different types of things. So that’s sort of the side that a lot of people pay attention to in relationship to the environment.

The flip side of the coin was also in seeing the impacts that were happening inside of communities. Growing up in Appalachia first and seeing some of the places that I really had enjoy being able to go hunting and fishing disappearing because of mountaintop mining really got my attention, and then seeing how people were getting sick also from chemicals, they were being exposed to in the water, land in the air. There were cancer clusters that were happening that nobody was ever talking about. Then growing up in a family of folks who are Baptist and Pentecostal ministers, that you have a responsibility to give back.

So my folks were very focused on that, very focused on worker rights, very focused on civil rights and a number of different issues and it just came altogether when I was a teenager when I first started working on these issues.

(0:06:23.6) AS: That reminds me of — I don’t know if you’re familiar with Wendell Berry. He’s a farmer, a Christian and he talks about like the way we’re going to make progress environmentally is when we get reacquainted with the land, right? Telling people that the temperature is rising is not going to motivate them the way that you’re describing being I a relationship with it of hunting and fishing and all that stuff, and I think that’s one of the things I love about your work in the Hip Hop Caucus is, it’s like, “Wait! This can be fun. It’s challenging,” but like we love the earth. We don’t just want to save it. It’s a great place to be in and I think we lose sight of that in our environmental conversations.

(0:07:00.5) MSA: We do. There are so many well-meaning folks in the environmental and climate movement, but sometimes the conversations that happen are ones that just don’t resonate with everyday folks, and it’s not that they don’t care, but it’s just like — So if you want to have a conversation with me about parts per billion or parts per million pollution, those types of things, it’s great information, but for Mrs. Ramirez, or Mr. Johnson, or Mr. O’Leary, it probably is not going to have a lot of meaning.

But if I talk to you about one of your favorite places and how it’s changing, maybe you had a fishing pond or a lake or a stream where you used to be able to go and catch fish and then bring them back to maybe the elders in your community and how that’s changing now, that has real meaning for you, or if there was a place that maybe you used to picnic or something like that and now it’s gone because of mining operations or because of fracking or a number of different types of things, then there’s that connection so that you can have that deeper conversation, or if you can see one of your relatives who are being impacted from pollution, then it’s going to get people’s attention, because there is that direct connection that exists in that space.

Sometimes we get so caught up in the wonkiness of these conversations that we forget about everyday people, what’s going on in their lives and how real change can actually happen. I think that that’s hopefully beginning to change, because younger people are getting engaged now, and artists are getting engaged and being able to create content that resonates with folks, that touches their spirit, touches their hearts and touches their minds.

(0:08:38.5) AS: Yeah, because when I was preparing for this interview, it’s like try to be pro-environment and all that stuff and I’m like, “Wait a second. What is even the end goal of climate change?” We’re looking at the Hip Hop Caucus’s work and studying about you. I’m like, “Wow! There’re so many end goals,” but I think, that to your point, gets — We talk about climate change, like the only goal is to stop the warming of the climate, but it’s really a more holistic look at what you’re describing of our community and whatnot, and that can make it so much more meaningful.

So I have a question for you then. So you’re talking about cancer clusters and whatnot and I actually had cancer as a teenager and my parents at the time highly suspected that it was from the pesticides and the yard chemicals that I was exposed to. Research now, 25 years, to your point, comes up that these are the connections, and I remember them going to our neighbors and saying — Because they were actually the only people in the neighborhood that didn’t get their yard sprayed.

I remember once I was diagnosed, they went to the neighbors, like each neighborhood and said, “Hey, this is a problem. We don’t want this to happen to you,” and it like fell on deaf ears. Now, I’ve been cancer free 25 years from now. The whole neighborhood, I’d say probably half of them have cancer, and they go to their doctors and their doctors go, “We don’t know.” Me, having a lot of incentive to get to root causes, I’m like, “Okay. You can say that.”

So how do you guys at the Hip Hop Caucus been effective at really making that connection for people when even though the narrative is changing in the mainstream, people on an everyday level, it’s almost like unless like God comes down and tells them, or their doctor, or the people who are authorities in their life tell them. It feels like it’s sometimes an uphill battle.

(0:10:18.0) MSA: Yeah. We’re all about just sort of reaching people where they are and having their experiences be a driver in the process and using cultural influencers. Cultural influences can be all kinds of folks. It could be someone from Common (inaudible 0:10:33.7), Chance the Rapper, all the way down to a local artist or a local person who owns the barber shop and the beauty salon and finding a way to elevate their voices really changes the game, because they are the ones that a lot of times folks value in, who are engaging with on a regular basis.

Then we bring in to those conversations with the artists also the scientific information. So to sort of help people once they made that connection but want to go deeper into it, then they have that opportunity to do that as well. Then, of course, it’s just sort of a re-informing that continually happens with the various platforms we have. We have something we call People’s Climate Music, which — I mean, just so many incredible artists are part of that, Common, Neo, Anthony Smith, Elle Varner. I can go down a list of folks.

When they share about what’s going on in the climate space, what’s going on in environmental justice, what’s going on around civil rights, or even some of the other issues that are now coming up, it’s amazing to see how that touches and connects with people and how people want to get more engaged in that space. So that’s really a powerful moment.

Then we also do the Respect My Vote Campaign, because we believe that the civic process has to be a driver and the change that happens in communities and the policy that’s being developed and how and where resource is slow. So we help people to understand the power that exists inside of their vote. Then we’re telling people who to vote for and to make sure that you are finding folks who care about your community, or you yourself get into the — Engage in the process and run for office yourself.

(0:12:24.6) AS: Yeah. I love that. Can you explain for the audience too what you mean by the environment and environmental justice, because when I was talking with your communications manager, he’s like, “It’s not just trees and bees, right?” So I love your holistic view of the environment. Can you talk about that and environmental justice?

(0:12:43.4) MSA: Sure. So let me break it down in two different spaces. So when we talk about environmental justice — And I was so blessed to be raised by many of the original environmental justice leaders. We’re talking about housing justice. We’re talking about transportation justice. We’re talking about public health. We’re talking about economic justice. We’re talking about the civic process and the voting process, and all of those things come together especially in our most vulnerable communities, because they don’t see these issues in a silo. So your environment is where you work, where you live, where you pray, where you go to school, all these various types of things. The environment is us and everything that surrounds us and how we interact with it.

Sometimes people get it twisted and they think, “Well, it’s just polar bears or it’s just icebergs.” Those things are important too, but it’s about real people and what’s going on in their lives and how our environment either helps us to be in a better place or it’s moving us backwards. So that’s the reason that we approach the issues the way that we do and it comes out of the work of the Environmental Justice Movement.

(0:13:52.8) AS: I love that. My husband is a writer and he was working on a book proposal with someone who used to be very prominent in public health, still is. Actually, got ousted by the pesticide industry because he was too honest. He was trying to write a book about the built environment, like where you decide to work and how you have to commute. Just everything that’s working against the American people. We were kind of joking like the title would be like We’re F’d, because (inaudible 0:14:18.7) environment, we’re like, “No American would buy that book,” and the book still hasn’t gotten off the ground, because when you really think about the environment in terms of not just the polar bears and the trees, you start to look at where’s — It like opens up everything. I think that’s the challenge and the opportunity, because I’m someone who loves to get to root causes, because if you get to the root cause, then you’re solving a lot of other problems along the way that you didn’t have to necessarily — I mean, it’s more work to solve the root cause upfront, but then you get much more return on your investment.

(0:14:51.4) MSA: No. I feel you on that. I just came back from Houston, Texas where I was speaking and I was sharing with some of the funders. So I was speaking at an event where the philanthropic family and funders were gathering together, and I believe in something called real talk. I say #realtalk

I share with folks that some of the challenges that we currently are facing in relationship to climate, if we had paid attention to our most vulnerable communities, we could have lessen these impacts, because many of the coal fired power plants are located in communities of color and lower income communities. Many of the greenhouse gas emitting facilities also are in those spaces. When we look at our transportation routes, we run huge amounts of diesel trucks and cars to certain communities and all of these things contribute to the warming of the planet, but they also contribute to these huge amounts of diseases that we see inside of these communities and the extraction of wealth from these communities.

So if we had done a better job 30, 40 years ago when many of our community leaders were saying, “Hey, these impacts are happening in our communities,” and folks wouldn’t pay attention at that time, maybe we wouldn’t be in this situation as in such dire straits as we currently are in relationship to climate if we had paid attention to what vulnerable communities were sharing with us three or four decades.

(0:16:23.9) AS: Yeah. I think that’s one — Coming from the holistic health space and working with a lot of clients who have chronic illnesses or someone like me who was a childhood cancer survivor, like we’re the canaries in the coal mine. You know what I mean? Vulnerable communities that you work with, and it’s almost like — I mean, there’s obviously racial issues of why we don’t pay attention as a whole, because we’re in a white supremacy culture and whatnot. But I think it’s really important for listeners to realize when you design for the most vulnerable communities, whether that’s people who are exhibiting chronic illness right now and their body can’t handle all of the pollutants, whether it’s people who have been marginalized because of their race or class. You’re really benefiting everybody. In fact, you’re getting a better solution.

Can you provides some examples for that? One of the things that my own wake up after the 2016 election is I basically stopped reading white people’s perspectives on things, because I’ve realized I was in a bubble and I had never examined my own race or whiteness, I guess. Even though I’m half Jewish, I learned that Jewish people aren’t considered white. I didn’t even know that. This is how much I wasn’t clear of this identity, but I’ve been realizing how much faster I learn and how many creative and beautiful ideas are out there the further you go out, because those communities can see that the normalization that is so unhealthy. Because I kind of come from a perspective that we live in a very sick culture. I should also let you know. The more that we can get out of the matrix, the faster the solutions can come.

(0:17:52.3) MSA: Yeah. I mean, real change can happen. We have the ability. We have the technology. We just have to prioritize, especially our most vulnerable communities if we want to actually get the biggest bang for our buck. I remember when I was working in the government, people do these cost-benefit analysis and all these other kinds of interesting formulaic ways of doing business. I often would say, “Well, if we invest in the communities that have the most challenges, who have the most air pollution, then we are naturally going to put the whole country in a better place.”

It’s interesting that if you look at some of the places across our country and the decisions that we made. So just to give some historical context. So there are things that are called restrictive covenances, redlining, all these different types of things that have in many instances push people into certain locations where we then have made decisions to just invest to have less enforcement, those different types of things.

If you look at places like Africa Town, which is outside of Mobile, Alabama, you have a place that was founded by freed slaves. So you hear people talk about freedom and communities, and then a number of tank farms then surrounded this community.

If you look at places like Moscow, Louisiana, where people literally have dioxins in their blood, and dioxins are cancer chemical. These again is a community of freedman, who actually saved, to be able to want to be free from slavery, and then to found their communities and now to be surrounded by petrochemical facilities. You can go up and down the coast from, probably, Virginia, all the way back over to taxes, we see these examples of these communities who have done everything right to be a part of this American dream, if you want call it that, but because of color of their skin or their ethnicity, a number of different challenges have been put in place. Then there’s also the flip side of communities that have been able to sort of turned the corner, if you will, and been able to revitalize our community. So hopefully we’ll talk a little bit about that too.

(0:20:08.2) AS: Yeah, I would love that. I mean, I saw an article going around — I mean, you’re saying you’re from West Virginia, about they’re starting to harvest lavender, where the mountaintops had been basically destroyed for coal. When I read that, I was like, “Damn! Mother nature is so resilient,” and like that to me is like such a metaphor of beauty right there. So I’d love to hear some examples like that.

(0:20:32.9) MSA: Yeah. Well, I mean there are a lot of communities that are making real progress. You have communities like — Well, we can look at it in two different ways. We could look at secular or we could look faith-based, as sometimes it takes different ways of sort of connecting with folks.

Sort on the secular side you have, and people heard me talk about this across the country, Spartanburg, South Carolina. A community that looks like many communities across our country that had transportation routes, had a shotgun housing. For those who are from the south, they’ll know what that means. You opened a front door, you could see out the back door. No energy efficiency, of course. You had also lack of economic opportunities in the community. You had lack of opportunity for healthcare. So seniors had to travel half an hour to get the healthcare, and number of other things. They had brownfields and superfund sites. So those are some of the most toxic sort of abandoned sites, they had a chemical plant.

It was interesting that when you went to this community, there was one way and one way out. So that’s the transportation route thing. So if there was an explosion that happened at the chemical plant, they told folks to do something called shelter in place, where you shut your windows and lock your doors and you stay and so people say you have the all clear.

Now, there’s a problem with that in South Carolina, that in the summer time it could be a hundred degrees and many people didn’t have air conditioning and you could run the air conditioning, even if you did, because if there chemicals that were being released, it would be sucked into your home anyway. So folks got together, the community began to say how they wanted to address some of their problems, but also the opportunities that they wanted to see inside their community. It took a $20,000 grant letters and over $300 million in changes. They now have new transportation routes with beautification programs which are part of it. They have five healthcare centers now in the surrounding areas. So seniors no longer have that long trek to try and get the healthcare. They have a new 50,000 square-foot green community center where students come and learn and also elders have a place to also come. So it’s a place of — It helps to strengthen the culture of the community. They have 500 new green homes.

Before, in that old housing that was there, folks in the summer time were paying $300 to $400 a month for their electricity costs. With these new green homes, we now got down to $67 a month. For folks who are on a fixed income, having those additional dollars are huge. The brownfields and superfund sites have been cleaned out and they’re now putting a 35-acre solar farm there. So that will now zero-out people’s electricity costs. It also lowers, of course, our carbon footprint and gives us an opportunity to move forward in that direction as well. They put worker training programs in place so that community residents were the ones who are being trained and were the ones who are doing the rebuilding. They did have a supermarket before and now they have a supermarket that has brought other businesses around it, because it’s sort of an anchor institution. So it’s creating additional economic opportunities.

Now we have a new STEM school where we have students ranging between 7-years-old and 18-years-old who have now been taught how to build androids, have also been taught how to build all of the parts that go as a part of windmills and then also solar. So these kids, once they finish this program, have the same level of education in this particular field as a first year MIT student. All of these things were driven by the community, which is a different paradigm.

You see these types of examples around the country. They just don’t get as much attention. The project I just talked about, the Regenesis Project, is one of the most successful environmental projects in the history of our country, but because it’s in a smaller or a rural area and we can say because it was an African-American led, I’m not saying that’s the reason primarily that it hasn’t got this much attention, but these are the stories and the narratives that if we begin to share them and people see that real change can happen and that there are intersection points for folks no matter what side of the isle you sit on, for those who care about the environment and climate, there is an intersection point for you, because you can see how that goes.

If you’re housing advocate, there’s an intersection point for you. If you are someone who cares about economics and job creation, there is an intersection point for you. That’s how we talk about and that’s how we move forward on these issues around the environment and climate, is by creating opportunities for lots of different types of foils to see how they can play a role and how real change can happen. This change can happen in West Virginia, or Kentucky. It can happen in the Rust Belt, in Michigan, or Wisconsin, Minnesota. It can happen along the Gulf Coast. But we just have to begin to prioritize that we are going to move forward and supporting these types of things.

(0:25:46.0) AS: That is so inspiring, and there’s so many things that you said that I kind of want to highlight, is first of all, find what interests you, right? We’ll have an environmental connection. I think about — On our podcast, we had my friends and someone, I most admire in the world, her name is Leah Lizarondo, and she started 412 Food Rescue here. Have you heard of it? I don’t know — Okay, yeah. She got into nutrition and stuff like that, but then that led to, “Oh my God! 40% of food in America is thrown out, and then we had people hungry. Look, you can make those connection,” right? It’s all about finding what interests you and then following that.

I think one thing that you said that reminded me of — I love the podcast On Being, and Krista Tippett had interviewed this nun who was also a social worker and a social justice advocate, but she said, “Americans think they need to do everything, and then they do nothing.” Like they get overwhelmed and then they do nothing.

What you were talking about at being community led, it’s like join with the people in your community. They are resourceful. You don’t need someone else to come in and give you a plan if you just start. Yes, it would be great to have people who can guide you and have some sort of acumen. But what I’m hearing is it’s like this giant metaphor of like when you rejuvenate the land and you rejuvenate the environment, you’re rejuvenating the community as well, and it’s part of the same kind of narrative that’s happening, or metaphor I should say.

(0:7:13.4) MSA: Yeah, I often talk about moving vulnerable communities from surviving to thriving. We have way too many communities right now who are in survival mode, but we can actually be supportive in helping people to move towards sort of a thriving sort of paradigm, if you will. But that means that — Let’s have some real talk here. That means that people have to be comfortable with power-sharing, and that’s gets really, really tough for folks, especially if we have some letters after our name. Sometimes we make the assumption that we know what’s best.

Communities have a wealth of knowledge, of innovation, and what they are looking for is folks to be authentic collaborative partners. I’ll say it again, authentic collaborative partners, because sometimes we call ourselves being collaborative partners, but we are not comfortable enough to give up the space for communities to lead, and then we bring whatever expertise that we may have as a supplement to what their vision is for the future, and that is a paradigm shift, if you will, that has to happen. In many instances, we want our local governments to lead a process, and yes, they have a role to play. But it’s those community members you have to make a decision about their neighborhoods, their area of what they want to see happen in that space.

So that is — I actually don’t think it is such a novel idea. It seems like it should be basics. I bet if you went and talk to kids on a playground, a kindergarten and said, “Would you like to make the decisions or would you like somebody else to make the decisions? I’m pretty sure that those five and six-year-olds would say, “I’d like to make my decision,” but unfortunately somewhere along the line of great planners and architects and policy folks and all these other folks are in the mix. We kind of lost our way and forgot that communities speak for themselves.

(0:29:07.0) AS: I would think that they are the ones who know the community, because they live there, right? Like there’s a certain domain knowledge and expertise that you have from living in that place. It’s kind of like, “Okay. This —” There’re so many nuances to the environment and I think we forget that. we think it’s just like seasons or what bus route on, and it’s like, “No. there’s so many dynamics that go on,” and communities are people at the end of the day, right? It’s human connection, which I know is really important.

I want to circle back. You emphasized authentic. Can you explain that a little bit? Where do things go wrong? I don’t work in a development space, the government space, so what do you mean by that?

(0:29:45.5) MSA: I describe authenticity the same way I describe like the relationship between a partner and a partner, boyfriend-girlfriend, husband-wife, whatever that situation is. to be authentic means to be present, and that’s tough for people, because sometimes folks like to parachute in, take some pictures, parachute back out, or run in with some ideas and then run back out. Being authentic also means that there has to be strong communication and a constant set of communication so you’re not just listening, but you’re actually hearing what’s going on. there also has to be trust, and when you don’t have that, you can’t be authentic, because if you break that trust, we’ve all been always relationship where we’ve had broken trust and we know how hard it is to get that back, if ever again. So that’s a part of that authenticity.

I try and keep things real basic and just help people understand things in a way of something that they probably went through in their lives, and that’s a part of that authenticity, being present, making sure that communication is there and all these other just basic types of things that really share with folks, if you’re serious about a relationship and that relationship is in helping a community to be better, stronger, more sustainable, more equitable, or if there are other sort of motives that are in that space.

I often tell folks, this stuff does not have to be rocket science. This is every day types of situations that you have went through probably since you’re a little kid up until the last time we take your last breath. If we see our relationships with each other, if we see our relationships with the environment in a similar fashion, it will make a lot more sense to a lot more people.

(0:31:34.0) AS: Yeah. I think being authentic with each other is often one of the biggest challenges, because I often think we’re not authentic with ourselves. We’re always kind of running away from ourselves. Not always, but it’s easier to do that.

(0:31:49.2) MSA: Yeah, not that we have to catch up with ourselves.

(0:31:51.7) AS: Yeah. I have so many questions to ask you. So you just wrote this piece where you were talking about getting into good trouble, which I love that, because to me, again, when I look at our society through a health lens and how we eat and how we stress and don’t sleep and how being at the — You were at the EPA, like in America you have to prove something isn’t dangerous versus proving it’s safe, which are very different criteria. You just wrote this great piece talking about some of these holistic issues with our health and how we don’t see them almost popping up, and you used the example of Freddie Gary. Can you share with people, because I really want people to understand how this environmental issue affects every level and why it’s so important to really do what you’re saying, is get involved, get into your community, be authentic. So can you share that, because I thought it was a very profound example?

(0:32:49.3) MSA: Getting into good trouble, one, we’ll start there. That’s just about standing up for what’s right, for embracing your morality and your humanity, and even when there are those forces that will push back against you, you know why you’re doing that. We’re so blessed to continue to have John Lewis who marched with Dr. King, who strategized with Dr. King and to be able to be in his presence that I have over the years is just such an honor to be able to really understand what that means.

We’re lucky that when we are out there marching or engaging, we don’t have to worry about someone throwing a brick and hitting us in the head or being sprayed with hoses or dogs chasing us, all those different types of things. So for folks today, it seems like it should be so much easier for them to stand up and to get into good trouble, to engage in our civic process, to engage in our democracy is our right. By doing so, we are helping to strengthen our country.

When you think about situations like with Freddie Gray and the impacts on pollution, the impacts from lead and how that followed folks in their communities throughout their lifetime. Being exposed to it at a very young age and then how it can cause neurological problems, lowering IQ points and other types of physical sort of ailments is one side of the coin. But once you get into a system where you can’t learn, and then if you start act out being sort of label in a certain way and put into a different track, it makes it so that you’re not going to be able to graduate high school, it makes you not going to be able to go to college in our country and can’t do that, the manufacturing jobs that were once there are no longer there. All these other dynamics begin to go on.

The story often goes that even if Freddie hadn’t been killed by the officer, the challenges were still there for him and others in his family, and you can even see that with Eric Garner. Eric Garner, who lost his life also to a policeman also had severe, severe asthma. Lived in one of the areas with some of the highest asthma rates. When the officers took his life by putting all that pressure on his lungs, he already had a very similar dynamic going on because of the exposure and because so many people lose their lives to asthma attacks.

So that is very much sort of parallel to what went on with Freddie also, and then unfortunately in our country, millions of young people have been exposed to lead. I think the last numbers I saw, maybe upwards of 5 million young people have been exposed to lead, and the huge amount of resources that go on the backend instead of us doing what’s right on the frontend and actually saving taxpayer money, but also saving people’s lives and giving them an opportunity to fully participate in being successful.

(0:36:03.3) AS: Yeah. I’m glad you brought that up, because especially for people who are listening and think, “Oh! Well, I live in a “good neighborhood” and I don’t have to worry about that stuff.” It is not true. My parents — Again, where I grew up as a “good neighborhood”, but I would call it a cancer cluster, Pittsburgh, because of the steel mills, the legacy of air pollution. We have some of the top cancer rates in the country. I think number three we might be, and it’s in large part from the residue of this Industrial Revolution that happened here in addition. But it’s amazing to me, again, the neighbors in my parent’s neighborhood, they were changing the water where my parents live and I’m like, “Mom, what is that chemical?” She’s like, “Well, I called up and the guy was like, “They just told us to put it in there.” I was like, “That’s not an answer.” I made them get a water filter that I researched.

Again, I wish more people would make this connection or like it’s everywhere. You know what I mean? Of this kind of stuff, and it affects us in these. It’s almost like a death by a thousand paper cuts, which is what I think you were describing with Freddie and Eric Garner. I mean, obviously police brutality is what ended their lives, but they were having problems because of air pollution, all of these stuff, and the school system is — All those things, and that puts major stress on the body. I know from trauma lends, when you grow up with all that kind of stuff, how it changes the brain.

I see that with my dad. He grew up in a very precarious situation growing up, and to this day like he still can’t handle like big noises or whatnot and changes and all that kind of stuff. I mean — So you just see — I’m like, “That probably happened from childhood,” and as you get older it’s hard control.

(0:37:51.0) MSA: We are living in an interesting time. We’re living in an interesting time because of the political things that are going on. If we want to talk about that, we can talk about that too. But also because there are so many scientific studies that are now coming out that are validating what folks have been saying for years. So we’re talking about lead right now. So there’s a recent study that came out in relationship to lead, and many times we focus on children when we talk about lead. Recently, a study came out that showed that now lead is being associated with hundreds of thousands of deaths with heart disease and impacts on the heart.

Folks should care about what’s happening in that space, because as you so aptly said, that this can also impact you. We’re starting to also see that through air pollution. There are all kinds of things that are going on with baby’s brains, with all of these diseases that are associated with air pollution now. The thing about air pollution is that there is an impact that happens, of course, to those communities that are frontline communities that are located right next to where the stacks are, but it travels, and it will have impacts across our country.

We live in a country right now where 140 million people live in areas where air pollution is out of attainment. We live in a country where 25 million people have asthma and 7 million kids have asthma. I can go on and on with the statistics, but the reality of the situation is, is that we have to make sure that we have strong environmental protections in place, but they have to be enforced. They have to be enforced in all the communities. When we don’t, we’re going to have generational problems that are associated with it.

We have problems with plastic now, these micro-plastics. There is a study came out the other that said 90% of our water has micro-plastics in it and is going to begin to affect us on a cellular level in our DNA. There are their scientists who are currently studying that, and that’s just one example along with a number of other chemicals that are in our drinking water even after it goes through our treatment system. Some of that is because we have old and crumbling water infrastructure systems. We have to invest in those. If we don’t, then what we’re doing is we’re playing with the lives of this generation, but definitely the generations to come because there will be additional impacts because of climate.

(0:40:27.5) AS: Yeah. So I do want to talk about the political situation, because you left the EPA because of the current regime. Reuters refers to it as a regime, and so they’re keeping track — Decline faster than I am. So I like to go to the sources. You left because of what’s happening, and I wanted you to talk about that because I’m kind of following how — The EPA has always had some issues. Like as someone who follows GMO’s and knows how Monsanto is very — Has their pool there as all lobbyists do and big pharm and all those. I’m trying to like — On my Facebook page, of my business Facebook page, I try to post these articles showing that Scott Pruitt is hiring a PR company with our tax dollars to basically spin a bunch of things. This week, Bears Ears just went to auction for these mining and drilling companies.

Can you explain the dynamic of how we have to keep our eyes wide open right now? Because, again, it’s not the one story that we’re like, “Oh! That’s ridiculous.” It’s like the narrative that they control over and over again, and pretty soon you think it’s more normal to drink orange Gatorade than a green smoothie.

(0:41:39.8) MSA: Yeah. I’ve been doing this work for over two decades now. So I’ve had a chance to work for a number of administrations both Democrat and Republican. I’ve never seen anything quite like what is currently going on. These folks — One of the reasons I left is because the decisions that they were making, I knew without a doubt, because of the experience and working in thousands of communities, working on policy, creating tools, all these different types of things, that the decisions they were making were going to make people sick. Unfortunately some people are going to die based upon these decisions that they were making. I knew that I couldn’t be a part of that because of the communities that I have worked for, come from and had served. But I understand others will continue to stay in the agencies and push and fight and scratch and try and make sure that the agency lives up to what it’s supposed to be, protecting health and the environment.

If you look at the decisions that are being made in relationship to superfund and trying to streamline that process, and superfund as we know are the most toxic sites, then you are going to leave gaps in that process. That’s sort of on the public health and the science side.

The other side of it is that the responsible parties are not going to pay their fair share, and they want a streamlined process so that they can get it done, the PRPs, and just be able to move forward. When you look at what they’re doing in relationship to science at the agency and devaluing science, eliminating science programs, cutting the budgets for science. That is intentional. It’s intentional, because then science and the law control the policy that’s being developed or not being developed.

So if you can eliminate science, then you can weaken the policy and you can achieve your goal of helping fossil fuel industries and others to be able to pollute more, to be able to maximize their profits without any concerns with the impacts on public health, because you have to have the science to be able to back up the decisions that are being made. You can go down the list around the stuff that they’re doing in relationship to water and the Clean Water Act and trying to weaken that as well. I literally have not seen one action that the agency has taken that is actually going to help people be in a better place.

Here’s my validator, if you will. So I’m literally out around the country every month, probably talking to at least 10,000. I asked a simple question every place I’ve been, from Main, to the middle of the country, to the West Coast, I asked, “Have you seen one action from this administration that has helped to improve the environment or helped to improve your health,” and I have not yet had one hand go up, and that’s the scary results that no one once has said that the actions and activities they’re doing has made me safer or healthier.

(0:44:42.5) AS: As you were talking, it reminded me, I read in Psychology Today, someone had done this article about if you looked at the personality profile of a corporation, it would be the personality profile of a sociopath. Since that, sociopaths are driven for one agenda. For corporations, it’s drive for profits. The same way that sociopaths emotionally externalize theirs costs, corporations externalize their environmental costs on to the public, which then we have to pay for.

I think people need to realize that, for those of you listening, when they say in this regime, “Oh! We’re cutting regulations.” I’m calling that protections, right? Same type of thing, because corporations do not have a responsibility to our environment. They have a responsibility to shareholders and they are considered people because of Citizens United.

It’s that shit crazy, but we take it because it’s been normalized. That’s one thing, like when did the environment and jobs ever become this like neutrally exclusive thing? What you were talking about with that amazing example in Spartanburg, South Carolina, is that when you revitalize the environment, you revitalize the economy, the community, education, all of that stuff. They’re not competing commitments.

(0:46:01.6) MSA: Yeah. Well, it’s great marketing that folks use to be able to sort of change the narrative and change the paradigm. It’s a false narrative, and here is why it’s a false narrative, because these are the old talking points that they’ve always use, that they’ve dusted off and that, for whatever reason, some folks are starting to trying to hold on to. The cigarette industry used to tell folks, “You could smoke as many cigarettes as you want and you won’t get a cancer,” and folks pump a huge amount of money into that to be able to sort of get every drip-drop of profit they possibly could out of that.

When we started to move forward on getting lead out of gasoline, they said that the auto market would crash, that our country would come to a standstill, and they put a huge amount of money into that. Of course, we got lead out of gasoline, everything — The economy continued to grow at a record pace. They did the same thing when it came to acid rain, and they used to say, “Well, if we do the technologies that’s necessary, then again, the economy is going to slowdown or shutdown, and they were wrong again. In that instance, you had lots of hunters and fishermen along with environmentalists and other people coming together to push for those changes to happen. It’s the exact same thing now, where they’re trying to make people make the assumption that if you have some basic environmental protections in place that keep people healthier and safer, then that’s going to taking jobs away.

There has never been any study with any validity that has been able to make that a reality. It’s almost like when they talk about climate change and 99% of scientists say it’s real and they go find somebody who says, “Oh, no! That’s not real.” They’re like, “Well, see? What did we tell you? Here’s Dr. X saying this.”

The problem is, is that places like the Environmental Protection Agency, they don’t have lobbyists, they don’t have a marketing firm. They’re supposed to do their job, and unfortunately you have companies that have billions and billions of dollars that they pump into these campaigns so that, as you said, they can maximize profits. Unfortunately, they’re forgetting that there are real people who will be impacted. But this is a new day. If you see what happened today in relationship to the Omnibus Bill, that — I think there were 100 different toxic policy writers that had been introduced trying to move into this space, because of all kinds of folks, men and women, students public health folks, environmental folks, civil foils, even folks who work in business and industry saying that, “You all are going too far. The things that you’re proposing are not going to help our country to be stronger and we’re going to push back against it.” All that attention was then moved to folks on Capitol Hill saying that, “Not only are we watching you, but that we are going to hold you accountable and that we will utilize our vote to make sure that if you can’t do your job properly, that will find somebody else who can, help to change what’s going on.”

For all of these egregious acts that folks have been trying to do in the environmental space, in the Environmental Protection Agency, from the White House, only a few of those have been able to find any traction, because of all of these folks saying that, “You will respect my communities, that I embrace my power and that I’m going to use it to hold a spotlight on what you’re trying to do,” and that’s the reason that they haven’t been able to do as much damage as they could have if men and women of good conscience had not got engaged in this process.

(0:49:57.2) AS: I love that you brought that up, because I was reading this article about the media likes to create this world versus city divide, but they were showing these farmers, these rural farmers who are pushing back at a local level on the EPA, because their concern for their farms and their animals. I was like, “Oh my God! This is like classic, divide the 99%.”

So we’re sitting here fighting while the 1% like ransacks like everything that matters — Not everything that matters to us, but I think that’s a great point and inspiration that you’re reminding, like people are fighting. What I found at least from the environment, working on the local level, you start to see — Like we have a plant neighborhood here who, since this regime came in, they were starting to report themselves, and now they’re not. It’s like to feel so much easier to get involved right now with (inaudible 0:50:46.2) environment and be like, “I want that — I live a mile away from here. I can smell the sulfur in the morning,” versus saying like, “Oh my God! How do I stop the warming of the earth?” It brings it down to that local level, or to your point, when we started off, like find what you’re interested in. I know some of our listeners, they got into the environment through looking at their makeup and how toxic it was. Now they’re campaigning on Capitol Hill to get these companies chemicals become out of our makeup. They also start coming out of the water systems and all that kind of stuff.

Just before I ask you another question, for those of you listening, if you are interested in what Mustafa referenced about the tobacco industry, a really great book written by someone who used to be in the EPA, is Dr. Deborah Davis, The Secret History of the War on Cancer. She actually lives in Pittsburgh, but she used to work in the EPA and she goes into detail how the tobacco industry basically play the American Medical Association, defy the public, and you will see that big food does that play book, everyone else that Mustafa just referenced.

It’s really good to know the play book, I think. It’s a pretty big book, but I think it’s worth the read so that you can feel empowered to get a little angry. I think it’s important to realize that anger can be really helpful and fortifying. I know it’s moved me into all kinds of action that is normally like — one of those like memes where you just don’t care any anymore. I mean, I care so deeply, which is wrong.

In wrapping up, like you have joined the Hip Hop Caucus, and I love what you guys — So one of the questions, I’m just going to put a white girl hat on. Do you consider Tupac hip hop? Because I think he was a prophet. His mom was in the Black Panthers and totally like educated him, but his song changes. Like I listen to that, and he mentions we got to change the way we eat, but he talks about war in the streets, not the Middle East. I was like, “Tupac was telling us everything that was happening.” I mean, I was like only in middle school to be able to like comprehend it. Do you consider Tupac hip hop?

(0:52:47.3) MSA: Oh, without a doubt. Without a doubt. I mean, the beauty of hip hop and the culture is that it is expansive. It captures so many different voices and so many different styles of expression and touches spirits and souls in so many different ways. If I’m in Japan, I see folks who are embracing hip hop and who are embracing music and embracing dance and dress and so many other aspects of culture, or when I’m in West Virginia, there is hip hop there, or when I’m in Kentucky, so many of the places.

The beauty of it, people like Tupac. Yes, many do feel like he was a prophet, because he was sharing, the reality of what he was seeing and what others were seeing, and that you can do something about it, and that expression is just powerful. From Tupac, to Biggie, to people like Talib now, or (inaudible 0:53:49.9) or Chance the Rapper, or so many others too. It is an opportunity for lots of folks to come together about what real change, and hip-hop traditionally had always been about calling out injustices that were happening, what folks were seeing in the streets, what folks were seeing in the barrios, what folks are seeing on the res.

We helped to support Taboo from the Black Eyed Peas with a video, I hope everyone checks out, called Stand Up / Stand N Rock #NoDAPL, which he’s talking about the water protectors, talking about pipelines, but also highlighting the voices of Native American rappers. That’s powerful in the culture that exists inside of indigenous communities and people and then being able to utilize hip-hop to be able to share these environmental impacts that were happening, cultural impacts that were happening, but how folks were going to stand up, not just for Standing Rock, but for other communities as well and push back and make real change happen, and that’s what hip hop is about. It’s about standing up. It’s about pushing back, but is also about being inclusive of all the different voices who are part of generations that continues to come into being and continue to fight to make our country and to make our planet better.

(0:55:13.3) AS: I love everything you share has this interconnected theme, like inclusive, like bringing people together. I think that’s a big part of your message is, is that almost like we each have our part to play and we’re all on the same team. Like, don’t we all want clean air, clean — All that kind of stuff, and we all have power to share, or power to give and to get involved?

What’s the most exciting thing that you’re excited about in terms of what you’re working on with the Hip Hop Caucus right now?

(0:55:42.0) MSA: Coming up here this Saturday, we are a part of the March For Our Lives. So I’m super excited, because it is a young people’s lead movement and they are saying that if folks won’t protect our lives, that we will. We’ll get engaged. We’ll continue to push. We’re going to vote, and we’re going to frame out a new direction. So I’m excited about that. I’m excited about the work that we’re doing with People’s Climate Music as well, working with all the artists and entertainers.

Just recently, working with the Black Eyed Peas with their new Street Livin’ video and series that they are doing talking about police brutality, talking about some (inaudible 0:56:21.9) industrials system and how it affects so many communities. Talking about DACA and immigration. So I hope folks will check that out as well, because it is a message that resonates throughout time, but also talks about how we have to make real change happen in our country.

I’m excited about our revitalizing global communities work, because even if we clean up a community, if stop an incinerator of a coal-fired power plant, there’s still a number of other dynamics and we have to make sure that we are supporting communities to be able to make the transformation that’s necessary. Our digress and invest work, I’m super excited about that. Trillions of dollars and now moving away from what I might call dirty portfolios to more efficient and clean portfolios. Then the recent radio show and podcasts that Reverend Yearwood and I just launched called Think 100%, which is really the message that we have to be about, moving towards 100% removal energy.

Also, when we talk about Think 100, #Think100, we’re also talking about keeping it real on these conversations that need to happen, moving to a more diverse, and whether it is then the big green organizations or building up the existing organizations so that we can make sure that we have institutions, so that we have these moments that they are translated into movements, because you have an institution that will be there a decade later. All of these different types of things that are going on are tools to help all of our folks be able to move forward in a positive direction. So I’m just excited. I am blessed to be able to be a part of the Caucus, all the incredible energy and creativity that exist in that space.

(0:58:06.2) AS: Yeah. I’m so glad you shared that. For those of you listening, checkout — And we’ll have all these links on my podcast page, but check out the Hip Hop Caucus. As Mustafa just shared, they have so many different entry points to get involved, or like he said earlier, find what’s interesting to you and follow that threat.

I was just looking on Instagram how I follow Glennon Doyle Melton I think is her name, and she was talking about she was at a rally for farmworkers and about fast food, and I was like, “Oh my God! I didn’t even —” There’s so many connections. If food is your thing, find what thread you care about, about farmworkers, or if it’s food waste, or if it’s about health. Find your thread and, I think keep following, which is it sounds like what you’ve done and it sounds like — Again, I don’t know the EPA, but Hip Hop Caucus sounds a little bit more fun.

(0:58:55.2) MSA: Yeah. No, it definitely is. I mean, I was a little different when I was there in the agency, as everyone will attest to. Not too many dreadlocks running around. You can make positive things happen everywhere. But it’s just so much — It’s just such a blessing when you can be surrounded by so many folks who not only get it, but are committed to not just this moment, but making sure that future generations have a platform, have a foundation and have an opportunity to just really make it happen.

(0:59:29.0) AS: That’s one thing I got into activism work, is specifically around the Affordable Care Act. I actually was in D.C. I was doing some press conferences and then some local stuff here, but I was like, “Oh my God! These are the people I need to be hanging out with.” I’m totally late to the party, I admit. Like I’m a late learning curve here, but I was like, “This keeps me so inspired,” when you see people who, they’ve been working at that stuff, and I just love supporting their efforts and pitching in where I can, because to your point about, I think instead of top down, like coming in and saying, “Here’s my idea.” I’m like, “Oh my God! How can I learn from you? Because you have been here and you know what to do. Tell me what you need versus like taking, feeling like I have to have all the answers, and I think that’s a lot of times what prevents people from starting. It’s like, “I don’t know anything.” It’s like you learn as you go and you don’t have to be the leader, which is the best part. Like there’s already great people doing great things, which is super inspiring, and so to thank you for sharing. That example in Spartansville — Wait, no.

(1:00:26.3) MSA: Spartanburg.

(1:00:27.9) AS: Yeah, South Carolina. I like want to go Google that now, because it’s just — Like you said, there’s probably hundreds more examples, and I think hopefully even though this current regime is doing that, I still see kind of almost people pushing back to your point and enough people know that like it’s kind of common sense, right?

(1:00:46.6) MSA: Without a doubt. I mean, look at the Women’s March, millions of women came together. People said, “Oh, no. They won’t.” Then women were like, “Oh, yeah. We got something for you.”

(1:00:54.8) AS: Yeah. Please, underestimate us. You won’t know we’re coming.

(1:01:00.1) MSA: The scientists are doing the same thing at the Science March. Nobody thought they come out their labs. They didn’t have a lot of rhythm, but they had a lot of heart. So I appreciate that. Folks are coming together and making real change happen. We’re holding ourselves accountable and others, and that’s what this is all about.

(1:01:17.0) AS: Wonderful. Any parting words for our audience or anything that I didn’t get to ask you that you’d like to mention?

(1:01:23.2) MSA: Just remember that you have power unless you give it away.

(1:01:26.7) AS: Ooh! I like that. Thank you, Mustafa.

(1:01:29.5) MSA: Thank you for having me. I really appreciate it.

(END OF INTERVIEW)

About Mustafa

-

Facebook

-

Twitter

-

Pinterest

-

Gmail

Mr. Ali worked for EPA Administrators beginning with William Riley and ending with Scott Pruitt. He joined the EPA as a student and became a founding member of the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice (OEJ) in 1992. In the OEJ, he shed light on environmental injustices across the country and worked across federal agencies to strengthen the government’s environmental justice policies, programs and initiatives.

Highlights from career at United States Environmental Protection Agency:

- 2014-2017: Led Federal Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice, comprised of 17 federal agencies and White House officials.

- 2012: Launched EPA’s Environmental Justice in Action Blog, with over 100,000 followers.

- 2010: Environmental Justice lead for the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

- 2007-2008: Served as Brookings Institution Congressional Fellow, focused on Foreign Policy and Homeland Security, Health Care, Veterans Affairs, and Environmental Justice.

- 2004: Selected as the EPA’s National Enforcement Training Institutes “Trainer of the Year” for efforts training over 4,000 people in “Fundamentals of Environmental Justice.”

- Has appeared on MSNBC, CNN, VICE, and Democracy NOW, and been featured and cited in over 100 news outlets to date, including GQ, New Republic, Ebony, Bustle, Guardian, The Root, Los Angeles Times, and Washington Post.

- Guest lecture at dozens of colleges and universities, including Harvard, Howard, Yale, George Washington, Georgetown, and Spelman.

- Former instructor at West Virginia University and Stanford University in Washington DC.

- Former co-host of the social justice focused “Spirit in Action” radio show.

Leave a Reply